Murat Soygeniş

This foreword to part titled ‘Physical and Sensual’ questions architecture and urban boundaries within the intersection of physical and sensual. How do we define boundary in architecture? How do we dream about and design boundaries as an architect?

The definitions of ‘boundary’ are many. A line indicating the limits of an area, a line dividing the areas, indicating the extent of a zone, a line on a map. Actually, one of these definitions is something that appears either in texts of geography or international relations such as dividing line between countries. Dividing line possesses deeper meanings. This quotation by a politician, ‘I will build a great, great wall on our southern border. And I will have Mexico pay for that wall.’ (Washington Post Staff, 2015) is quite self-explanatory revealing the hidden agenda behind a boundary. The word ‘border’ or ‘boundary’ and how it is referred to in this case somehow create fear, tense atmosphere and it is threatening. Here the word border strongly indicates a separation, a division. The meaning of separation, a cold physical border reminds us of dislocated millions, questions about humanity and values, which happen in different parts of the world due to wars, economic, and political problems. Actually, the world history is full of unfortunate stories about borders.

Historically city walls have provided security for the inhabitants against invaders in the past. People, in order to create a safe environment, constructed walls, boundaries free for some group of people and not allowing others. The Berlin Wall as a boundary element meant separation for a nation, a strong indicator of a polarized world. People had cherished its demolition when it was taken down, letting people cross borders freely, hoping for unification of people globally. (Fig. 1)

Looking into nature, it is possible to see the terrain with its boundaries where mountains border valleys, valleys border mountains in such a dynamic way, that produces spatial perceptions, experiences of variety in nature, a three-dimensional complex pattern. Besides the physical boundaries, there are invisible boundaries between human beings and in nature. The immaterial boundary between seasons is a representation of the complex order in nature and is an indication of time and continuity. The Bosphorus in Istanbul creates a natural boundary between two continents. It physically separates the two lands, yet at the same time connects the two parts of the city creating an in-between space, maybe an interface that gives a charm to the city of Istanbul. (Fig. 2)

Besides the topographic potentials of the earth, architects and urban designers create manmade boundaries in cities over time. For example, modern city has created its boundaries by zoning as residential, business district, agricultural area, and others. The edges, nodes and paths, as mentioned by Lynch in his book, ‘The Image of the City’, are the physical manifestations of manmade boundaries in a city. People get to perceive urban environment through the manmade boundaries. The spaces or the voids of the urban fabric can be classified as paths and urban squares. It is how the boundaries are defined either as directional as paths or more like gathering places as urban squares that define how space is perceived and experienced. It is the space or void, and the enclosure of urban spaces and the spatial layout of the cities that human beings form their visual memories of a city. It is the details and materiality that appeal to all the senses and form the perception of spaces.

Today, architects face with the dilemma of how to deal with boundaries in urban environments. How to restore the boundaries that have created memory over the years on the inhabitants of a city? Public spaces reflect the relationship between space, time and people that can be traced on public spaces of cities. Various traditions, belief systems and value judgments have shaped the forms of the past. Concurrently, public spaces while transforming in time reflect the change of time and ways of living. What is crucial is the extent of transformation and how it happens. Restoring the old is a way of keeping the continuity of history and urban memory. ‘All experience implies the act of recollecting, remembering and comparing. An embodied memory has an essential role as the basis of remembering a space or a place.’ as Pallasmaa states (Pallasmaa, 2005, p. 72).

Concurrently, architectural examples of the past are important sites for exploration for the present. They recall memories, guide to understand and appreciate the cityscape. The point to remember is an awareness on the value of the existing faces of the urban environment as quoted by Boyer, ‘… a better reading of the history written across the surface and hidden in forgotten subterrains of the city’ (Boyer, 1994, p. 21), which asks for re-examining and recontextualizing the past for new paths to the future. In this context the crucial point is to restore the existing boundaries in order to preserve the sensual qualities of the urban spaces of the city that provokes one’s memory. As stated by Pallasmaa, ‘We have an innate capacity for remembering and imagining places. Perception, memory and imagination are in constant interaction…’ (Pallasmaa, 2005, p. 67).

Concern for privacy or survival are revealed in a variety of ways as boundaries throughout history. Architects have created bordering elements and boundaries from primitive to complex, being either conservative or innovative at times. Architectural history is full of variety of manmade examples of boundaries. People of Anatolia have bordered spaces separated from its surroundings for survival as in the Cappadocia example in Turkey where enclosure is naturally formed. The space is carved to create an interior form with limited voids for structural and security reasons. Over the course of architectural history, boundary that forms interior space have evolved depending on the changing social aspirations and availability of technology and materials used in forming the boundary. Emphasis of vertical and horizontal elements in creating an enclosure, a border, a boundary or an interface between interior or exterior have been used extensively by modernist architects as a form of materializing space. A boundary may be just physical, very concrete, or as immaterial as to imply the threshold, foreshadowing meanings and evoking memories. Openings, voids on the boundary, the material quality of the boundary and how it is constructed are the means in creating the sensual of the physical.

Modern architecture had a bias towards visual nature of design. Yet, there are examples where the design responds to the other senses as well. Mexican architect Luis Barragan’s boundaries or walls act as objects in space, with bright colors foreshadowing their location and the climate they are in. ‘There is a subtle transference between tactile and taste experiences. Vision becomes transferred to taste as well; certain colors and delicate details evoke oral sensations.’ (Pallasmaa, 2005, p. 59). A more symbolic example, Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC by Maya Lin, with its black granite wall lines the earth to create a space of memory. The wall forms a threshold between the earth and the walkway. It pays a tribute to the martyrs. It is an information board to be read, a reflection of sorrow and a reminder of war and death. In some architectural examples, architectural boundary elements like solid walls, waterfall walls, artwork walls, lead the pedestrian to various perceptions of space and artwork. Architecture becomes more of a story of a boundary and then a void or a space. Bordering walls, waterfalls, or art walls create a medium of rich perception for visitors. Void on the boundary is ‘… a mediator between two worlds, between enclosed and open, interiority and exteriority, private and public, shadow and light.’ (Pallasmaa, 2005, p. 47). Thus, physical boundary element acts as a tool in creating a sensual experience for the people experiencing the space.

Architects have been facing with the dilemma of keeping the local and historical boundaries that has formed the face of the urban environment and at the same time create new boundaries according to the changing needs of people. The challenge is how to form new boundaries that are adequately physical, permeable, inviting and sensual?

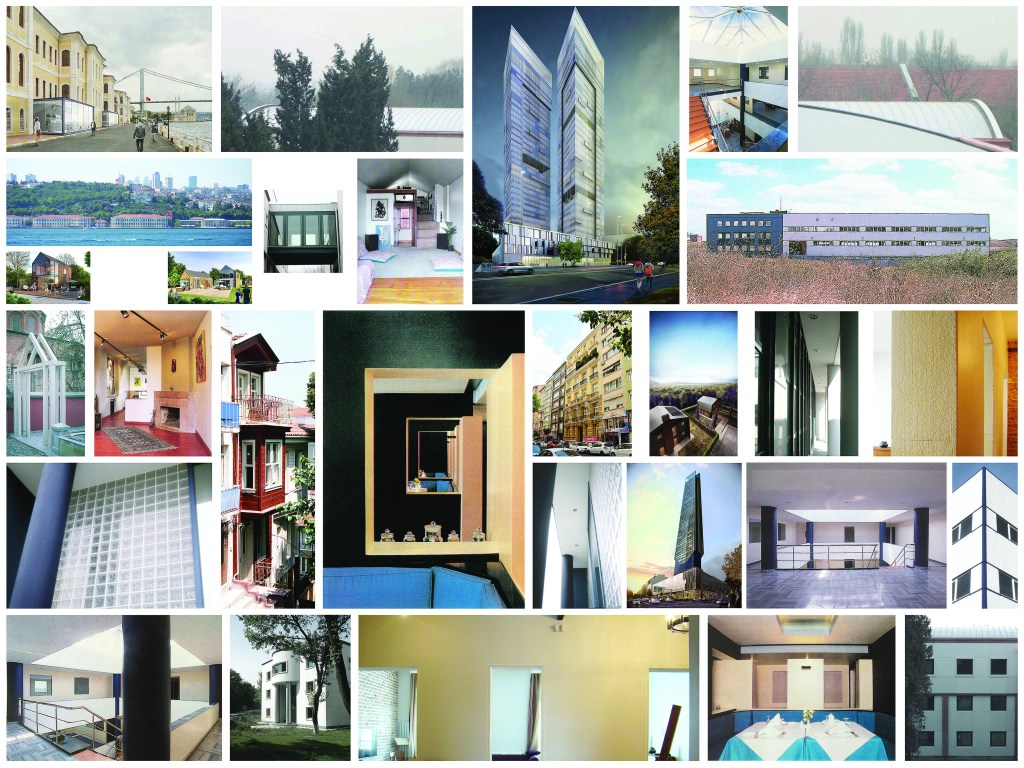

In our design work at S+ ARCHITECTURE, one of our concerns is how to read and interpret the existing context with its physical and sensual potential. In a series of built and unbuilt projects in Istanbul, London and Mexico City, we continue to experiment with walls, surfaces, textures, colors, and a continuous spatial experience of interior and exterior within the realm of surrounding cityscape to create uninterrupted manmade and natural environment. Depending on the location of the project, potentials of both the existing historic and urban environment have been our concern keeping in mind the power of memory in creating space with sensual qualities (“S+ ARCHITECTURE”, n.d.). (Fig. 3)

In a loft conversion in a busy downtown district, the existing old brick wall was kept with its original texture, contrasting the new, plain walls that help to intensify the texture of brick wall, a reminder of the past. In a narrow house on the Bosphorus, the linearity of the open interior space was emphasized by the design and detailing of one of the side walls as a continuous display wall in gray color contrasting other walls. In an early project, a restaurant in an existing historical building neighboring the Byzantine church museum, Chora, we wanted to create a new interior in contrast to the historic character of the building and urban space. It was an attempt to display the existing in the presence of the new and vice versa. We experimented with walls, colors with the intention to treat an enclosure or a wall beyond its physical content to imply perception responding to visual and tactile senses also displaying itself as a separate element from the existing building. In this restaurant project, the consequences of the existing space almost asked for play of walls. The solution was to play with solids, voids, rhythm, contrast of dark and light, lively and pastel hues. To reinforce the spatial unity and visual linkage between the entry area to the restaurant yet to preserve the privacy of booths and tables, walls were designed with modular rectangular voids enriching the light quality of the space with color differences. Free standing wall became an object in space with the ceiling floating over corridor and entry area. Similar projects with the spatial experiments followed; a pavilion named ‘maze’ in a park, an academic complex, industrial plants, miscellaneous projects for an Ottoman Palace, mixed-use projects, modular houses for refugees.

Architectural boundaries define activity areas, spaces and order people’s lives with their physical and immaterial potential. Physical becomes meaningful with its sensual potential opening way to various perceptions and to memories. Following works by two artists and sculptors, Fred Sandback and Jaume Plensa, may be meaningful examples for architects to explore.

An artist, a minimalist conceptual-based sculptor, known for his yarn sculptures, Fred Sandback’s work can be inspirational with a deep reading of his work. He creates almost invisible sculptures or installations that do not have an inside, and he finds the means to ‘… assert a certain place or volume in its full materiality without occupying and obscuring it.’ (“The Art Institute of Chicago”, n.d.). His sculpture named ‘Untitled’ occupies the physical site as an invisible plane. He uses string and a little wire to represent the outline of a rectangular solid plane. These invisible planes are sometimes standing upright, sometimes leaning against a wall, just like huge glass panes. It can be viewed from different perspectives. He states that ‘It incorporates specific parts of the environment, but it’s always coexistent with the environment as opposed to overwhelming or destroying that environment in favor of a different one.’ (“Fred Sandback Archive”, n.d.). Sandback creates in his artwork an immaterial plane, that can be perceived in variety by the viewer, appearing and disappearing while moving in space. It appeals to the senses and questions the idea of border in the memory. (Fig. 4)

Spanish artist Jaume Plensa poses a different approach. With an awareness of body’s embodiment of the soul, he has created work that expresses bordering. His sculpture titled ‘Alchemist’, ‘… made of randomly arranged stainless steel letters of the alphabet… in the shape of a person sitting with knees drawn up to the chest.’ is a ‘… homage to all the researchers and scientists that have contributed to scientific and mathematical knowledge.’ (“MIT List Visual Arts Center”, n.d.). The physical boundary made up of letters embodies the soul that is yet to be explored and felt.

In light of these issues, I encourage all readers to discover the five chapters in Physical and Sensual that follow. The chapters concentrate on urban aesthetics, fading boundaries in school design, invisible boundaries of periodic markets, border between perceptual and physical urban space, and the future sociability issues in public spaces. In an age of commercialism and globalism in architecture, isn’t it worth concentrating on nature and nature of human beings, with all the potentials?

References

Boyer, M. C. (1994). The City of Collective Memory Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Fred Sandback Archive. (n.d.). 1973 Notes. Retrieved November 12, 2018, from https://www.fredsandbackarchive.org/texts-1973-notes

MIT List Visual Arts Center. (n.d.). Alchemist. Retrieved September 15, 2018, from https://listart.mit.edu/public-art-map/alchemist

Pallasmaa, J. (2005). The Eyes of the Skin. West Sussex, England: John Wiley and Sons.

S+ ARCHITECTURE. (n.d.). Profile. Retrieved May 20, 2020, from https://www.splusarchitecture.com/profile

The Art Institute of Chicago. (n.d.). Untitled. Retrieved October 10, 2018, from https://www.artic.edu/artworks/160221/untitled

Washington Post Staff (2015, June 16). Donald Trump announces a presidential bid. The Washington Post, Politics. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2015/06/16/full-text-donald-trump-announces-a-presidential-bid

Murat Soygenis, FAIA, a founding partner at S+ ARCHITECTURE, is an architect/professor practicing in Istanbul. He received his architectural education in Istanbul, Turkey (B.Arch., PhD, ITU) and in Buffalo New York, USA (M.Arch., University at Buffalo). Over the past 35 years, he has served at numerous administrative positions including on the Boards of AIA Europe, and as the Dean of School of Architecture of YTU. His publications focus on his teaching, research and practice, and include 12 books and monographs, over 100 authored writings in books, journals and periodicals, receiving more than 100 citations globally. Professor Soygeniş has produced more than 150 professional projects, lectured widely to share his views on architecture and urbanism. His professional work has been exhibited at significant venues in Istanbul, USA and Europe including the American Institute of Architects, and received design awards from many institutions including the RIBA – Royal Institute of British Architects. He is a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (FAIA), a member of the Chamber of Architects in Istanbul (UIA), and the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA).

Source: Soygenis, M. “Boundaries and Spaces: Physical and Perceptual”, The Dialectics of Urban and Architectural Boundaries in the Middle East and Mediterranean (S. G. Akdag, M. Dincer, M. Vatan, U. Topcu, I. M. Kiris, Eds.), Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2021, pp. 169-176.